Positioning and Acquisitions

An acquisition – for both the acquiring company and the company that has been acquired – is a golden opportunity to revisit and tighten up positioning. Post-acquisition, the context of both the acquired and the acquirer often shifts. It makes sense that we would want to review the positioning to determine what might need to change. I will cover a set of common post-acquisition positioning scenarios and end this article with a few key additional things I think companies should consider.

Post-Acquisition Go-to-Market Strategy Will Impact Positioning

How a product’s or company’s positioning needs to shift after an acquisition depends on the company’s intended go-to-market strategy post-acquisition. There are choices to be made, and it isn’t always obvious how best to position a new product relative to the company’s existing offerings. In this article, I will explore some possible scenarios and how I’ve seen companies tackle positioning. This list isn’t exhaustive – I’ve seen some weird one-off edge cases – but I will hit the most common ones. Hopefully, this guide will give you some ideas to chew on whether you are part of an organization that has recently acquired something new or you are on a team that has been acquired.

Five Post-Acquisition Scenarios

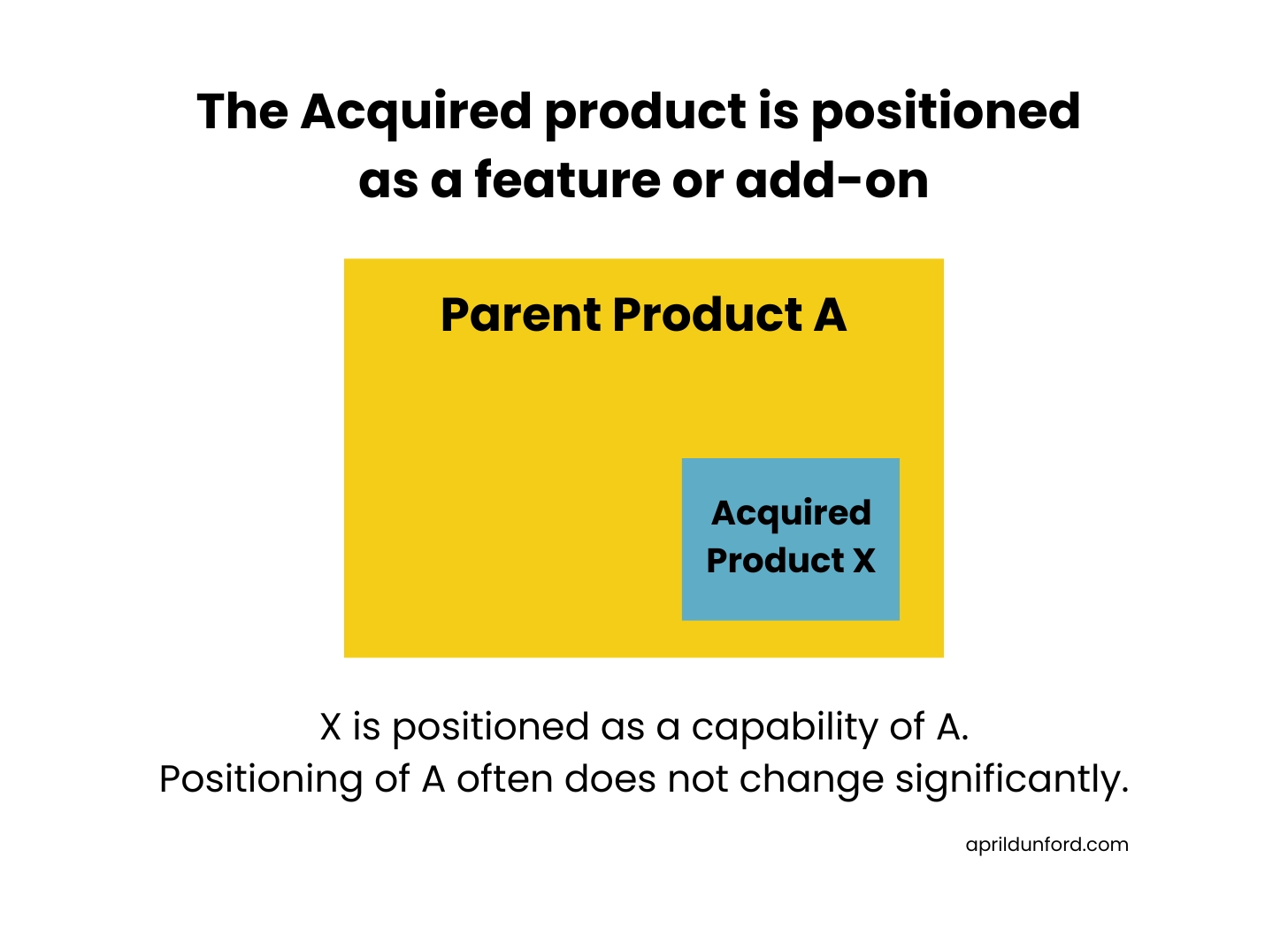

Scenario 1: The new product becomes an add-on, extension, or “feature” of an existing product.

This situation is fairly common where a very large company acquires a much smaller one and the goal is to extend the functionality of one of the acquiring company’s products. Often, the newly acquired product will no longer be positioned as separate from the parent product. It could become a fully integrated feature of a parent product or an addon that is either free or paid. In general, the new product will no longer need its own separate positioning, as it will never be sold separately from the parent product to a customer.

We don’t need to position every new feature or add-on.

If the new product becomes an optional add-on (particularly one that customers pay for), the sales and marketing teams will need to understand the value that the product delivers that would justify selecting it. That being said, most companies would simply position the add-on’s capabilities and corresponding value as part of the overall parent product’s capabilities and value. Put another way – the parent product is positioned such that the capabilities of the add-ons are included, and the individual add-ons do not need their own positioning separate from the parent product. (Aside - this holds true for new features that the teams develops internally. In general, only critically significant and differentiated features warrant their own positioning or a name – and often not even then!)

If the new product adds significant new value that the parent product did not previously deliver, then you will want to adjust the positioning for the parent product, just like you would for a major new product release that adds new value. If the new product merely strengthens an existing value pillar for the parent product, then no significant shift in positioning is needed. The new capabilities can be slotted under the current value themes they support.

Add-on vs. upsell/cross-sell

In my opinion, if a paid add-on alone adds significant separate additional value to the parent product, or buyers might consider competitive products instead of buying the add-on – then you might want to consider positioning this product as a cross-sell or up-sell to the parent. We will cover this in the next scenario.

Scenario 2: The new product becomes an up-sell or cross-sell to customers of an existing “wedge” product.

In this case, the newly acquired product is positioned as a fully separate product (not as a feature or add-on), but is rarely sold to any company that doesn’t already own a particular “wedge” product from the parent company.

A wedge is an easy way to crack into a new account.

This is a fairly common go-to-market strategy for larger, established companies that have a product that is a clear market leader and other products that are challengers in their respective markets. For example, for many years, if Salesforce was selling into a new account, they were not trying to sell anything beyond the core Sales Cloud CRM product. That product was (and still is) the clear leader in the CRM market, making it an easy sell to wedge into a new account. Once the product was deployed in the account, then they would focus on selling Marketing Cloud or Service Cloud (apologies to anyone reading this that might work at Salesforce today – I know this has changed since the acquisition of Slack. I’m just using it as an example tech folks know about). For Marketing and Service Cloud, the positioning could piggyback on Sales Cloud. Marketing Cloud for example, didn’t need to be the world’s greatest marketing automation platform, they could position it as the world’s best marketing platform for companies that already use Salesforce’s CRM product.

A wedge strategy narrows the positioning for the other products.

With this go to market strategy, the new product post-acquisition, will need to be positioned with the specific assumption that anyone buying the product will already own the wedge product. This often changes the value of the new product significantly. On the other hand, because the wedge was always positioned fairly independent from the rest of the company’s offerings, its positioning will not change much post-acquisition.

You might shift your company positioning….or not.

Lastly, the company might want to refresh its overall company positioning – or not. Many companies that use a wedge product strategy focus most of their company positioning around the wedge. Others will emphasize the full breadth of products. If the latter is true, then the company will need to re-visit its overall company positioning post-acquisition.

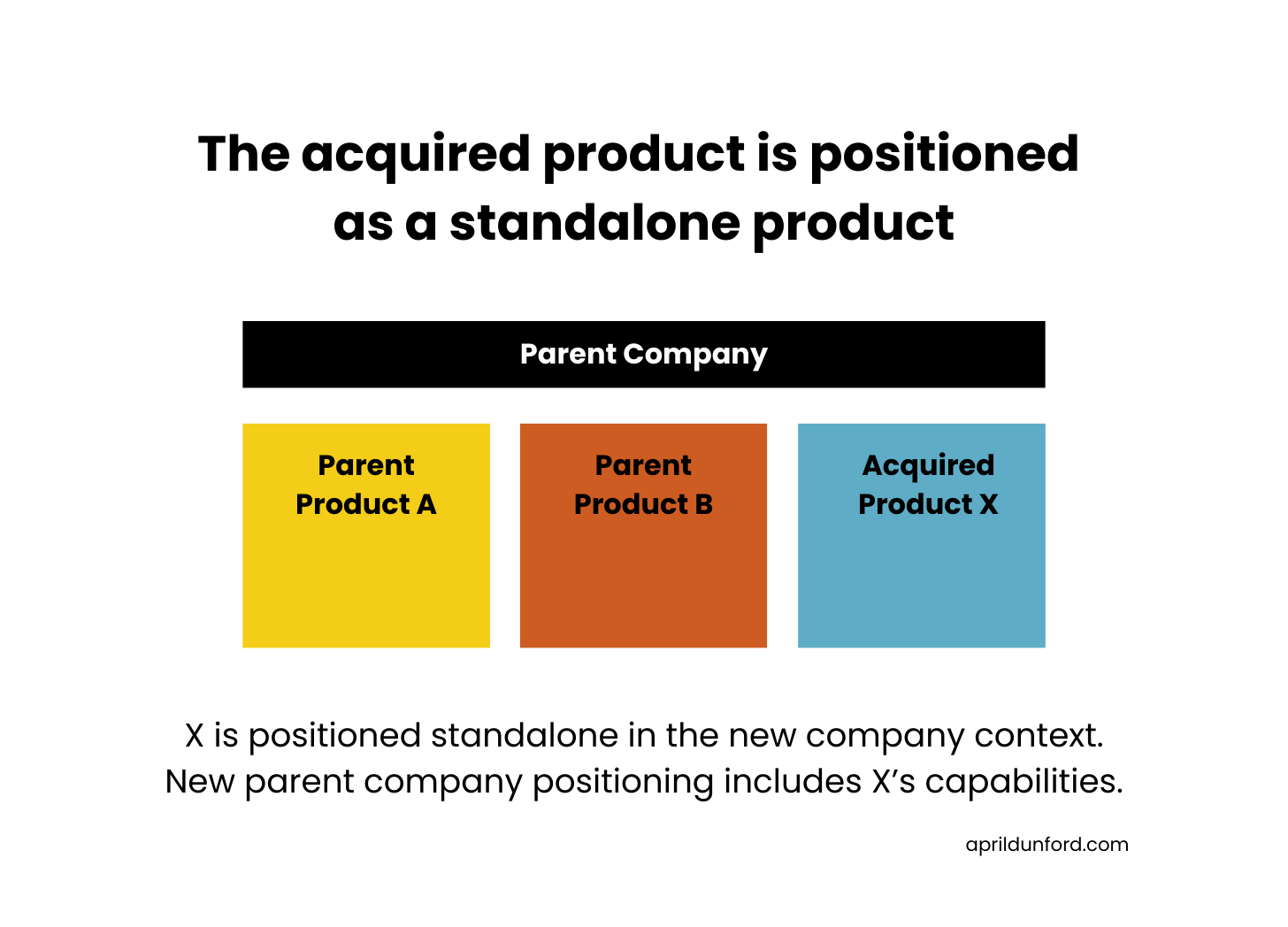

Scenario 3: The new product becomes its own standalone product, entirely separate from the other products in the company’s portfolio.

In this case, typically, the company has a set of products, and each one is aimed at a market distinct from the others. For example, the company sells a logistics solution for shipping companies and a different logistics solution for railroads. They then acquire an ERP for trucking companies. The company positioning will need to expand to include the new offering – in this case, perhaps they will evolve from positioning themselves as logistics management for long-haul transportation to a broader position around transportation logistics now that they serve both long and short-haul providers.

New product context, new positioning.

In this scenario, the positioning of the acquired product might change a little or a lot from what it was pre-acquisition, but it likely will need to change. Although the new product is likely purchased standalone for the most part, there can be significant value to customers now that it is sold and supported by a larger company. For example, there might be improved international support, additional professional services, different financing options or guarantees that the acquired company did not previously offer. For this reason, the company will want to look at the newly acquired product’s positioning to make sure that it accurately reflects the full post-acquisition value for customers.

Don’t forget potential bundles.

Positioning the product as part of a combined offering may also be needed. Using the example above, there might be cases where the customer’s needs span both rail and trucking, and the sales team would need to be able to tell the story that spans the company’s offerings. If this is the case, the company will need new positioning and a sales pitch for the combination.

Scenario 4: The new product becomes part of a family or suite of products already sold by the acquiring company.

If the acquiring company serves the same target market as the new product it has just acquired, often that new product will be positioned as part of a broader market “family” or “suite.”

Maximizing our revenue per account.

For example, suppose the parent company has a suite of tools for food manufacturers, including an inventory tracking solution, an accounting solution, and an order management solution. To add to the suite, they acquire a company that does data analytics and reporting.

Each of the products might be priced and purchased separately, but often, the sales team will want to expose a new prospect to the whole suite to try to maximize the size of the deal by selling them multiple products. The prospect might only be interested in one product today, but we want to ensure that they know what they can get from us when other needs arise. After the acquisition, the company will need new positioning and a sales pitch that tells the story of the new suite, including the new analytics and reporting product.

New context, new positioning (again).

They will also likely need new positioning and a sales pitch to help the team sell the analytics product on its own when the opportunity arises. As we talked about in the previous section, even though the product is the same, the new context of the product – as part of the parent company and part of the suite – will likely mean that we need new positioning and a new sales pitch.

5/ The new product becomes a part of a “platform” sold by the acquiring company.

Companies use the word “platform” in many different ways. In the pure sense, I’ve always considered a platform to be more integrated than a suite and is architected to be easily extended by 3rd party software. That said, I have seen a LOT of software products that claim to be a “platform” that have none of those characteristics and, to me, looks exactly like a suite of products.

What’s a platform anyway?

In general, I think the word “platform” means more to those of us in tech than it does for most customers. In tech, we have been trained to understand that a platform has certain properties (the components are tightly tied together technologically, it can be extended in some way by third parties, there is some sort of common technology or data backbone across the platform, etc.). In my experience, customers rarely see a significant difference between a “Suite” and a Platform, and therefore, it’s our job as vendors to educate them.

If the parent company has a platform, there will be some positioning choices to make after an acquisition. Should the new product be positioned like a separate product add-on or a fully integrated part of the platform? Is the new product potentially going to be sold as a cross-sell or up-sell to the platform? Are we actually calling this a “platform” but positioning it like a suite at the end of the day? Companies will want to be very clear about how they expect to go to market and choose the positioning that best helps customers understand the relationship between the platform and the newly acquired product. Only after those decisions have been made can we determine which of the earlier-mentioned positioning scenarios we should apply.

Two Other Important Considerations

A positioning exercise is a golden opportunity to align the teams.

I’ve worked with dozens of teams on post-acquisition positioning, and the CEO tells me that aligning the teams on the new combined story is hugely valuable. There aren’t many formal opportunities to get folks from across marketing, sales, and product – from both sides of the acquisition – together in a discussion around the competitive landscape, differentiated value, and ideal prospects. The education in these sessions generally flows both ways, with the parent company better understanding what worked at the smaller company pre-acquisition and the newly acquired team gaining insight into how the parent thinks about the market landscape and how to win.

Developing a combined pitch the sales team believes in is CRITICAL.

As an in-house marketing exec, I worked on both sides of a dozen acquisitions, and as a consultant, I’ve worked with more than 50 teams on post-acquisition positioning. If there is one thing you really need to get right after a product has been acquired, it’s the sales pitch. You can spin a great story in your press release and have marketing build super-compelling copy and campaigns, but you’ll never make your acquisition business case if the sales team isn’t on board. The sales team must understand the value of the new product in the context of what they already know how to sell. If they don’t, they will simply ignore it and carry on as if the acquisition never happened. The best way to solve this problem is to have sales involved in creating and testing a new pitch that reflects the new combined positioning.

Does this line up with your experiences? Sound off in the comments! And if you appreciated this post, don’t be afraid to “like” it!

Season two of my podcast is out. My favorite episode so far is with the CEO of Postman. Check it out here (or wherever you get your podcasts).

Summer hasn’t really started yet, but I am already booking workshops for September and October. If you are struggling with your positioning and want to chat about how we might work together, you can book some time with me here.

I will be in lovely Edinburgh, Scotland, in July for TuringFest - see you there?

Thanks again for reading - I appreciate you!

Thanks for the thoughtful peace, Toby!

Thanks for this April, appreciate this content. My company has gone through 3 acquisitions and telling a multi-product story for 3 different audiences is hard! I totally agree that a company should have sales, marketing and product aligning post-acquisition, otherwise people just continue selling what they know. another thing to think about is level-setting the knowledge about the product suite across these teams and PMM playing a central role in that alignment.